The long-toed salamander is a rare sight in Waterton.

Last month, I swung a pulaski for the first time. Okay, not so much swung it, as hacked and chopped and dug with it as I helped repair the salamander fences and tunnels in Waterton.

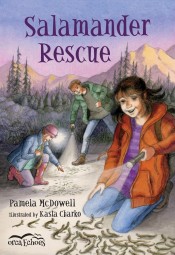

Parks Canada offered something new during the Waterton Wildlife Weekend this year – the opportunity to volunteer. And, wouldn’t you know, my next book, Salamander Rescue, is about these same salamanders!

The only road into Waterton village cuts right through the long-toed salamander habitat, and bisects their breeding migration route between Linnet Lake and Crandell Mountain.

The roadway endangered Waterton’s salamanders, exposing them to cars, predators, and salt. The slightly lighter coloured strip across the road here is the top of the tunnel.

In 2008, four ‘tunnels of love’ were installed under the entrance road. Catch fences line the roadway, directing the salamanders to the tunnels. It’s been a few years now and erosion and weathering have created gaps under the fence and widened crevices between the fence and tunnel openings. Salamanders don’t need much space to sneak through. Sadly, the little critters will follow the fence to the mouth of the tunnel, then scale rocks and vegetation to cross the road on top of the tunnel!

Matt Adams stand at the base of Crandell Mountain and tells us about his salamander research.

So under the direction of Parks Canada employees Kim and Will, and Matt, a University of Alberta biologist, we set off to repair the tunnel entrances with plywood, chunks of rubber, a handful of bolts and rebar.

The first task was to clear out vegetation, sediment and rocks that had been washed into the mouth of the tunnel. This is where I discovered the usefulness of the Pulaski.

A Pulaski combines an axe and adze in one head, creating a tool often used in fighting wildfires. It was named after Ed Pulaski, an assistant ranger in the U.S. Forest Service in 1911.

We needed to leave a layer of dirt to cover the concrete floor of the tunnel, but ensure there was enough space between floor and ceiling to install a motion-activated camera at a later date.

Air slots allow sunlight and moisture into the tunnel, creating inviting passage for salamanders, snakes, rabbits, and even raccoons.

Next, we used plywood to close the gap between the side of the tunnel and the fence. The cross-section of a culvert is an ingenious, low-profile fence for redirecting salamanders, but it’s a bit challenging to align curved metal with vertical concrete and leave no gaps.

A smooth vertical surface prevents salamanders from climbing onto the road.

Don’s MacGuyver skills were very useful during this project.

Don and I completed the hillside openings of two tunnels in about three hours. In April, when the salamanders come down from Crandell Mountain to breed in Linnet Lake, I hope more of them will make the trip safely. And I hope we’ll be invited back to finish repairs on the remaining two tunnels.

And…. next April you can read all about the saga of Waterton’s long-toed salamanders in Salamander Rescue, my new chapter book from Orca Books.